For those not familiar, Horus Binary is a high altitude balloon telemetry system. It’s goals is to overcome some of the challenges compared to other general purpose systems as high altitude balloons have unique challenges.

Challenges with high altitude balloon telemetry

Telemetry is important to track the location of the balloon to aid in recovery, but also to downlink data in case recovery isn’t possible. Often several payloads are flown and some flights contain multiple communication methods, not just Horus Binary. As with the majority of things mentioned in this post, the RF downlink is a series of compromises specifically chosen to solve a problem. For example you can run an entire DVB-S transmitter and have a live feed of the video footage - but for this you need yagis and a fixed location - limiting the possibility of recovery without another solution.

It’s pretty common for a high altitude balloon to reach 30km altitude. So even if you are standing directly under the balloon at that time, it’s some distance for wireless communication. While the distance is pretty great, the advantage of being a balloon is there’s rarely any obstruction between the receiver and transmitter - so we win back a little bit of SNR from having the line of sight advantage. To handle the distance we want something with a low baud rate and error correction. While typically we have line of sight, we still want to receive telemetry at launch and landing, where conditions might not be perfect for RF.

Balloons can only lift so much. Large balloons require more helium, more expensive, harder to launch and may require more regulation/rules. So the payload also needs to be light. Launching a IC-7100 radio isn’t a great option. But down sizing also imposes some more challenges. Smaller payload means less battery, less transmit power. Horus Binary is often transmitted from repurposed radiosondes, powered by one or two AA batteries with an RF output power in the tens of mW. The lighter transmitter solution allows for more weight dedicated to science.

Now one of our key requirements is trying to recover payloads. This means we want to receive a telemetry packet on, or as close to, where the payload hits the ground. We could build a system that let you send kilobytes of data - but at the low baud rate, it would take forever to send. These balloons are falling at rates around 20km/hr, so if we receive a packet every minute then very likely we might not receive a low enough altitude packet to accurately determine the landing location and recover the payload. So we want to keep the payload size short.

So what about existing infrastructure, like satellite, cellular , LoRa networks. These actually do get used on flights, but they have their shortcomings. For cellular there might not be coverage at the landing location, and since cell towers generally point their antennas down or to the horizon the coverage can be patchy in the sky. For satellite there’s weight constraints for high speed links, and for most small trackers the update rates can be minutes or more. LoRa is a similar story with low update rate (if being a good citizen) and you need to rely on good area coverage. So if we aren’t using existing infrastructure, then we need to bring our own. That means having recovery vehicles able to easily receive it, and a network of stationary receivers where possible.

For a mobile receiver this means we don’t want a fancy multi element yagi tracking system. We want a simple dipole or cross dipole that can used on a moving vehicle. Likewise on the payload, we want an antenna with little gain in any one direction, as we won’t be sure which way the antenna is facing.

Summary of requirements

- Low SNR requirement

- High update rate

- Reliable data

- Low power usage

- Mobile receiver

This results in some of our design constraints for a protocol:

- Low bit rate (100 baud)

- Small packet sizes (< 128bytes)

- Low power transmitter

Horus Binary v1/v2

Horus Binary v1/2 have been around for awhile now and pretty well established in the amateur high altitude ballooning space. It uses a well tested 4FSK 100 baud modem with Golay for error correction. The payload itself is 20 (v1) or 30 (v2) bytes, with an additional 2 bytes for a checksum.

Anyone can receive the telemetry by using either a sideband radio receiver or software defined radios like the RTL-SDR, which keeps hardware costs down.

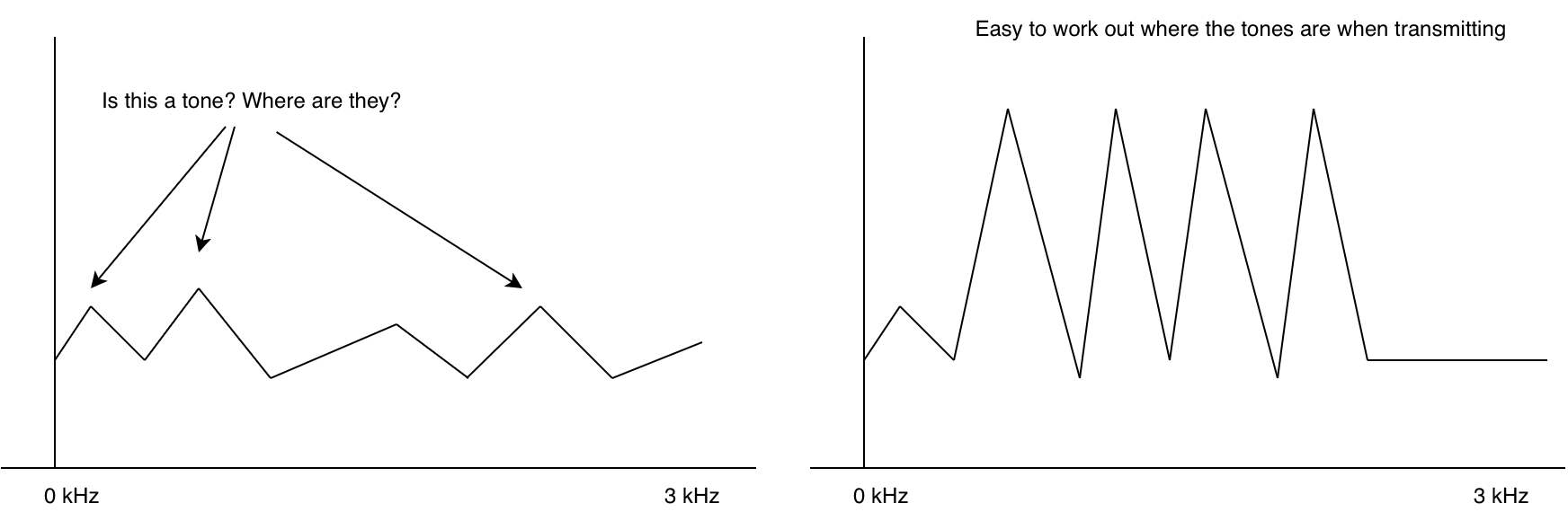

We don’t need to dive too deep into RF for this post as this modem is well established and pretty good quality, but we do need some quick fundamentals. Horus Binary uses 4 times frequency shift keying (4FSK) - or put another way, 4 tones to indicate ones and zeros.

If you tune a radio to a frequency where there’s no station, you hear noise. This is also true for data modems. Without any sort of checking we’d get a random string of ones and zeros. (sometimes this is used to generate random numbers!). In fact without anything transmitting the modem doesn’t even know where the signal/tones are.

This is why at the start of an RF packet, often we transmit what’s called a preamble. A sequence that is super easy for the modem to figure out where the tones are. With the modem synchronized, the next problem is decoding. The modem itself doesn’t really know whats valid ones and zeros and whats invalid.

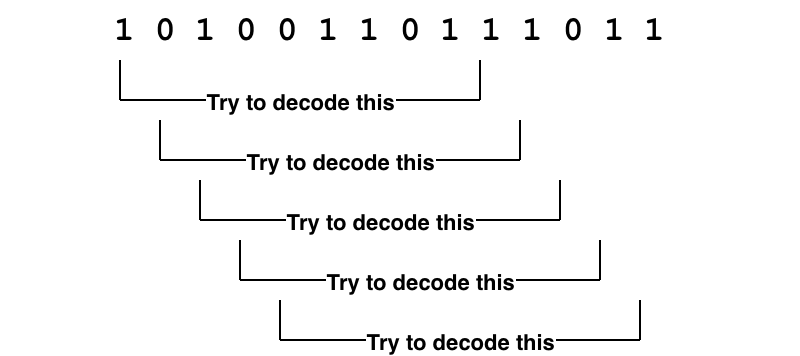

If we take the ones and zeros and try to decode each one and check its checksum, then we would waste a lot of CPU and possibly not even keep up with the incoming data. We really need a way of quickly seeing if a packet is actually likely to be a packet.

For this we use a “unique word”1. A series of bits that are always at the start of a packet. We can accept a few of these bits to be wrong due to noise by setting a threshold of valid bits. Effectively don’t try to decode the packet unless the unique word is at the start.

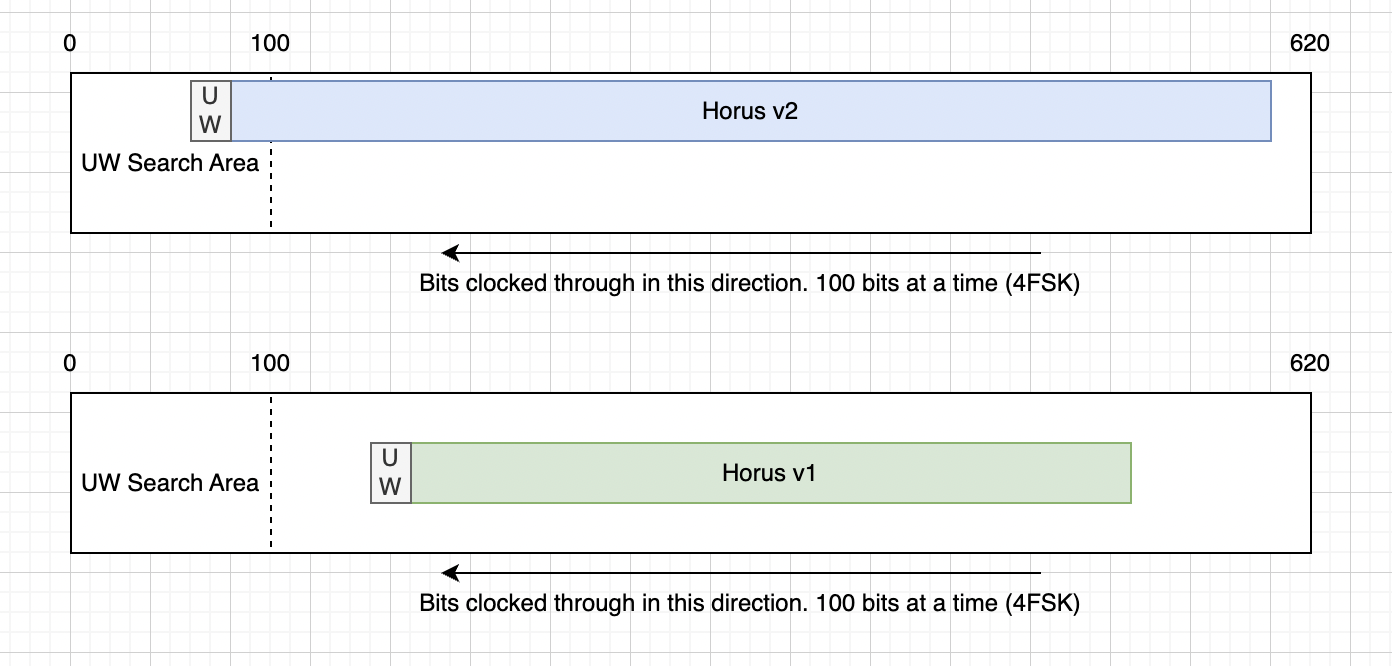

Putting this all together for Horus Binary v1/2 we have

<preamble> <unique word> <payload> <checksum>

0x1B1B1B1B 0x2424 DATA(30) CHECKSUM(2)

Horus Binary v2 payload data

30 bytes is not a lot. So what is in there, and how do encode/decode it? For v1/v2 a simple struct packing is used. The table below shows how the fields are stored. By packing the data down as binary data without any tagging or delimiters a lot of useful information can fit inside a small packet.

| Byte No. | Data Type | Size (bytes) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | uint16 | 2 | Payload ID (0-65535) |

| 2 | uint16 | 2 | Sequence Number |

| 4 | uint8 | 1 | Time-of-day (Hours) |

| 5 | uint8 | 1 | Time-of-day (Minutes) |

| 6 | uint8 | 1 | Time-of-day (Seconds) |

| 7 | float | 4 | Latitude |

| 11 | float | 4 | Longitude |

| 15 | uint16 | 2 | Altitude (m) |

| 17 | uint8 | 1 | Speed (kph) |

| 18 | uint8 | 1 | Satellites |

| 19 | int8 | 1 | Temperature (deg C) |

| 20 | uint8 | 1 | Battery Voltage |

| 21 | ??? | 9 | Custom data |

The astute among you would have noticed the “Custom data” field. If there are no delimiters or field separators in the format, how does one decode that data into fields again. Like wise the Payload ID seems to be a number, rather than a callsign - but on sites like SondeHub a callsign is displayed.

Horus Binary v1/2 rely on two files that are regularly updated to resolve the payload ids to callsigns and the rules to unpack the custom data. This means that receiving stations need to have internet access prior to the flight to get the latest data and launch operators need to submit pull requests to get their callsign and custom data allocated.

The smallest a custom field could be was a byte.

Handling different sized payloads

Horus Binary v1 and v2 use different payload lengths, however receivers don’t need to configure which version they are receiving. How does that work? We try both

In v1/v2, we have a buffer that is just longer than the longest packet. As data comes in we shift the bits to across so that new data is always on the end of the buffer. Then we search the start of the buffer for the unique word. If we see the unique word, we try decoding both Horus Binary v1 and v2 - Only one of the checksums should pass, if it does, then we have a valid packet.

This however means that we have to wait the same period of time for v1 packets as we would for the much longer v2 packets.

v1/v2 shortcomings

Now lets summarize some of the shortcomings for v1/v2

- Launch operators require a central authority to bless their callsign ID and custom payload data

- Receiving stations need to regularly phone home to get latest configs

- Custom payload data is rigid and inflexible

- There is latency in decoding smaller packet sizes

- Small size of 30 bytes can limit usefulness for some missions

Additionally the software for decoding Horus Binary had some issues:

- Pypi packages didn’t have wheels, resulting in users having to build their own versions

- The modem itself is a C executable which had to be built separately

- Horus GUI Windows app required reusing a handcrafted DLL, limiting ability to update the modem component

- Limited testing / no testing framework meant a lot of manual testing before releases and changes

While still meeting the constraints listed above, can we do better?

Horus Binary v3 and ASN.1

This is where Horus Binary v3 comes in. Horus Binary v3 is an attempt to address the above issues and has taken months of planning, discussions, development and testing. Most of which has been figuring out which things to compromise on. While apps today are running entire browsers and gigabytes of memory, the development of Horus Binary v3 meant squabbling over single bits, let along bytes.

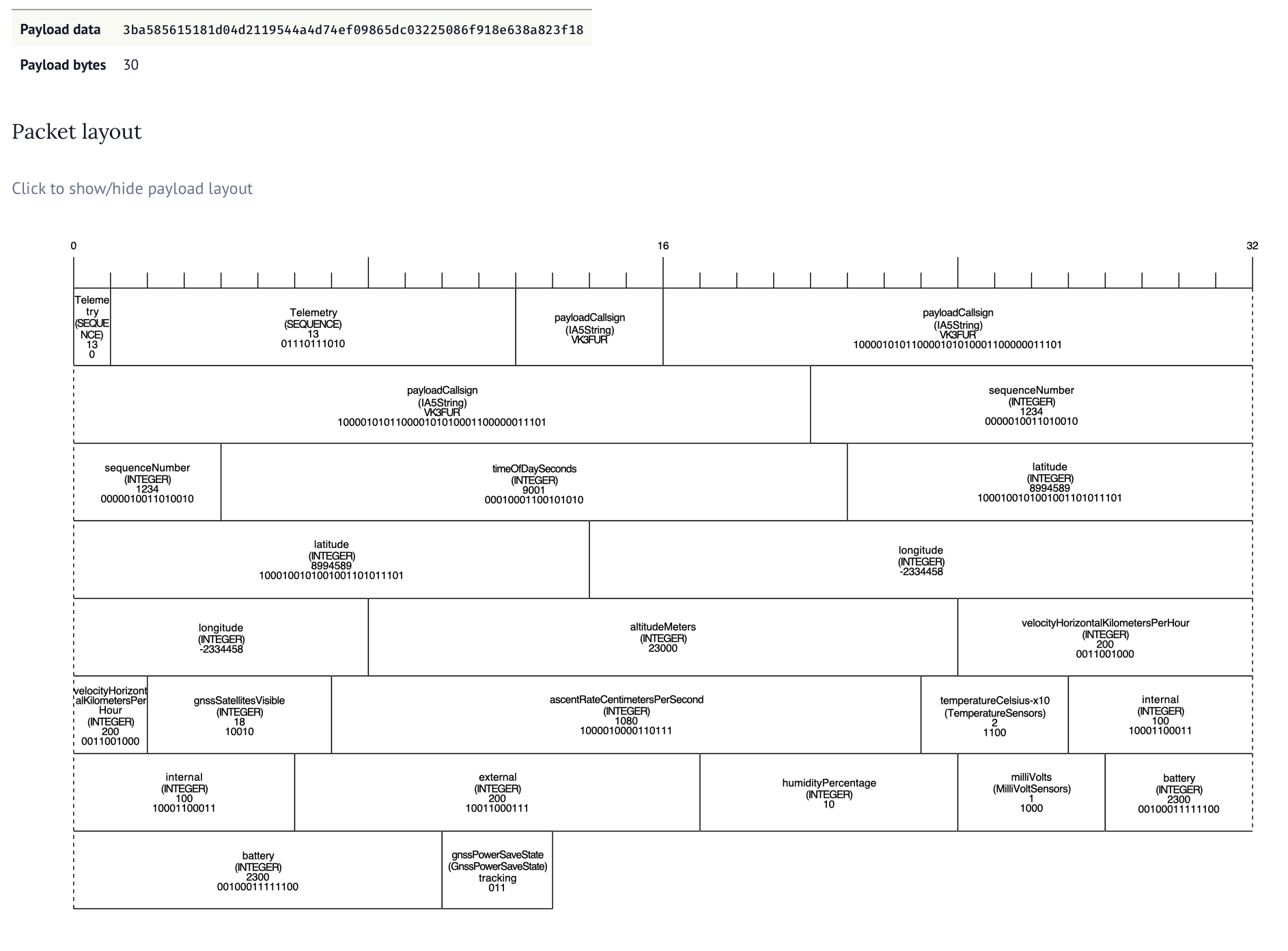

One thing I wanted was a well defined specification of the binary format. After investigating things such as protobuf, Cap’n Proto and many other encoding schemes I was somewhat surprised to find there’s limited options for unaligned formats. Unaligned means that a field doesn’t need to be whole bytes. A field can start and stop at any bit offset, rather than a multiple of 8. Shifting from a byte aligned to unaligned format was important to the design goals as it let use save bits from fields that would otherwise need as much range in their values. Eventually settled on ASN.1 using it’s Unaligned Packed Encoding Rules (UPER).

ASN.1, or Abstract Syntax Notation One is a standardised way of describing data.

For example I can describe a temperature field like so:

internalTemp INTEGER (-1023..1023) OPTIONAL

In this example the internalTemp field can have a value from -1023 to 1023, and it is optional.

ASN.1 defines a bunch of encoding rules. We can take the above specification and encode it into XML, JSON, or bits. What’s great about UPER is that it takes into account the size constraints like (-1023..1023), so that the final encoding for that field is just 11 bits long for the data itself. The optional flag is an additional field to mark if the field is actually present. So if internalTemp isn’t sent in the payload, then only a single bit is consumed.

Encoding a value of 123 for internalTemp results in 12 bits:

Optional flag Number

1 100 0111 1010

From experience we know that several fields are always sent - such as Payload ID, sequence number, time of day, location. But we also know that each payload is different and will may have none, one or multiple of sensors like temperature, voltage, pressure, counters. We can place these fields into our specification and operators can pick and choose what they need.

CustomFieldValues ::= CHOICE {

horusStr IA5String (FROM("abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789_ +/=-.")^SIZE (0..255)),

horusInt SEQUENCE(SIZE(1..4)) OF INTEGER,

horusReal SEQUENCE(SIZE(1..4)) OF REAL,

horusBool BitFlags

}

AdditionalSensorType ::= SEQUENCE {

name IA5String (FROM("abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789-")^SIZE (1..20)) OPTIONAL,

values CustomFieldValues OPTIONAL

}

AdditionalSensors ::= SEQUENCE(SIZE(1..4)) OF AdditionalSensorType

Additional to the built in sensor types, we also have an AdditionalSensors field which uses ASN.1’s CHOICE function to allow an operator to pick what kind of data type they require. This could be a REAL, INTEGER, BOOLEAN or a STRING. This allows some amount of self describing without the need of central authority.

Since fields and sensors can be optionally added and removed a payload doesn’t need to send all it’s sensor data down, all the time. While location is important for recovery, sensors can be sent sequentially to fit in packet sizes.

Payload IDs have also been replaced with strings. While this consumes more bytes it allows freedom to develop and launch without having to request a payload ID number. ASN.1 UPER rules allow us to define what characters are allowed, and by doing so this reduces the per character cost to just 6 bits per letter.

To help develop the format and understand the packet length costs we built a tool to visual the ASN.1 encoding. Along with a series of unit tests to make sure the encoding was working ok.

The tool allows for changing the ASN.1 specification and input data, allowing payload developers to make decisions on what data to send when and can be found here. It took a lot of collaboration and thought to figure out good compromises. Adding an optional field always consumes one bit so we want to work out which fields are always sent and which ones might not get sent. If we made every field optional we would waste nearly an entire byte in optional flags.

For each field we want to also constrain the size of that field - this means figuring about the absolute min and max values for each type along with the required resolution. I wish ASN.1 had support for fixed precision.

But 30 bytes still doesn’t get us much data. What if we have a bunch of extra sensors.

Longer packets and checksums

We’ve expanded out the packet size to allow 32, 48, 64, 96 and 128 byte long packets. While we don’t recommend sending 128 byte packets as the transmission time is longgggg, it’s an option for those who need it. The 48 byte packet seems like a really nice middle ground balancing the packet size with additional telemetry.

But this long packet poses a problem with the current solution. The latency would increase significantly if we have to wait for the longest packet size before checking all the combinations.

This is why we’ve flipped around the way the packet is attempted to be decoded. As soon as a particular format has enough bytes to decode, we try to decode it, regardless of where it is in the buffer. By switching to scanning for the unique word as the bits come in we are able to decode all packet sizes with the smallest amount of latency.

There’s still one problem though. If we have a 32 byte packet that could be v2 or v3, how do we work out which decoder to use? Our final change of the telemetry format was to move the checksum to the start of the packet. So we check the checksum at both the start and end of the packet. If the one at the start passes, it’s v3 and if the one at the end passes it’s v2.

Transmitting

It’s all well and good being able to generate these complicated unaligned structures in Python on a machine with gigabbytes of RAM but we need it to run on a repurposed microcontroller. For this we use the ASN1SCC compiler.

This can take an ASN.1 specification and turn it into light weight C code.

// some setup and error code removed for brevity

horusTelemetry testMessage = {

.payloadCallsign = "VK3FUR",

.sequenceNumber = 2,

.timeOfDaySeconds = 30,

.latitude = 90,

.longitude = 90,

.altitudeMeters = 1000,

};

horusTelemetry_Encode(&testMessage,&encodedMessage,&errCode,true);

The ASN1SCC is pretty light weight compared to other tools like asn1c and asn1tools. We saw an increase of roughly 6 kilobytes to the compiled output.

Two problems with ASN1SCC is that it’s opinonated about space vehicles. This means that extension markers are currently out of scope and not supported but we were able to work around that placing a dummy optional field. The other is that ASN1SCC assumes you might build a packet that is as long as the longest possible - causing excessive memory usage. We worked around this by building our own assert handler and allowing smaller buffer sizes.

Packaging and tests

There’s three main way Horus Binary v3 is received. Using horusdemodlib’s horus_demod command in a shell script, webhorus in the browser and the horus-gui desktop application.

Horus-gui uses horusdmeodlib which demodulates the signal using libhorus C library. The result is that for both horus_demod shell script method and horus-gui options, C code needs to be compiled using cmake. This means extra compiler tools to install and extra steps for the user to follow.

An additional concern that by using ctypes to access the library in Python there is risk in programming errors causing subtle memory corruption bugs that are hard to catch. We have to carefully define all the arg and return types for each function call like so.

self.c_lib.horus_set_freq_est_limits.argtype = [

POINTER(c_ubyte),

c_float,

c_float,

]

self.c_lib.horus_get_max_demod_in.restype = c_int

To resolve these issues we made the change from ctypes to cffi. This makes Python in charge of the compiling, and automates the creation of a library which handles the args and return types correctly. Additionally we converted the C based horus_demod command to Python.

With Python now in charge of compiling we could start using cibuildwheel to automate making Python Wheels (these are precompiled ready to go packages that are built for each desired Python version and architecture). This means the majority of our users do not need to compile to install and use horusdemodlib and simplifies the build process for horus-gui.

A user can now do pipx install horusdemodlib to install decoding and uploading utilities2. No compiling needed in most cases.

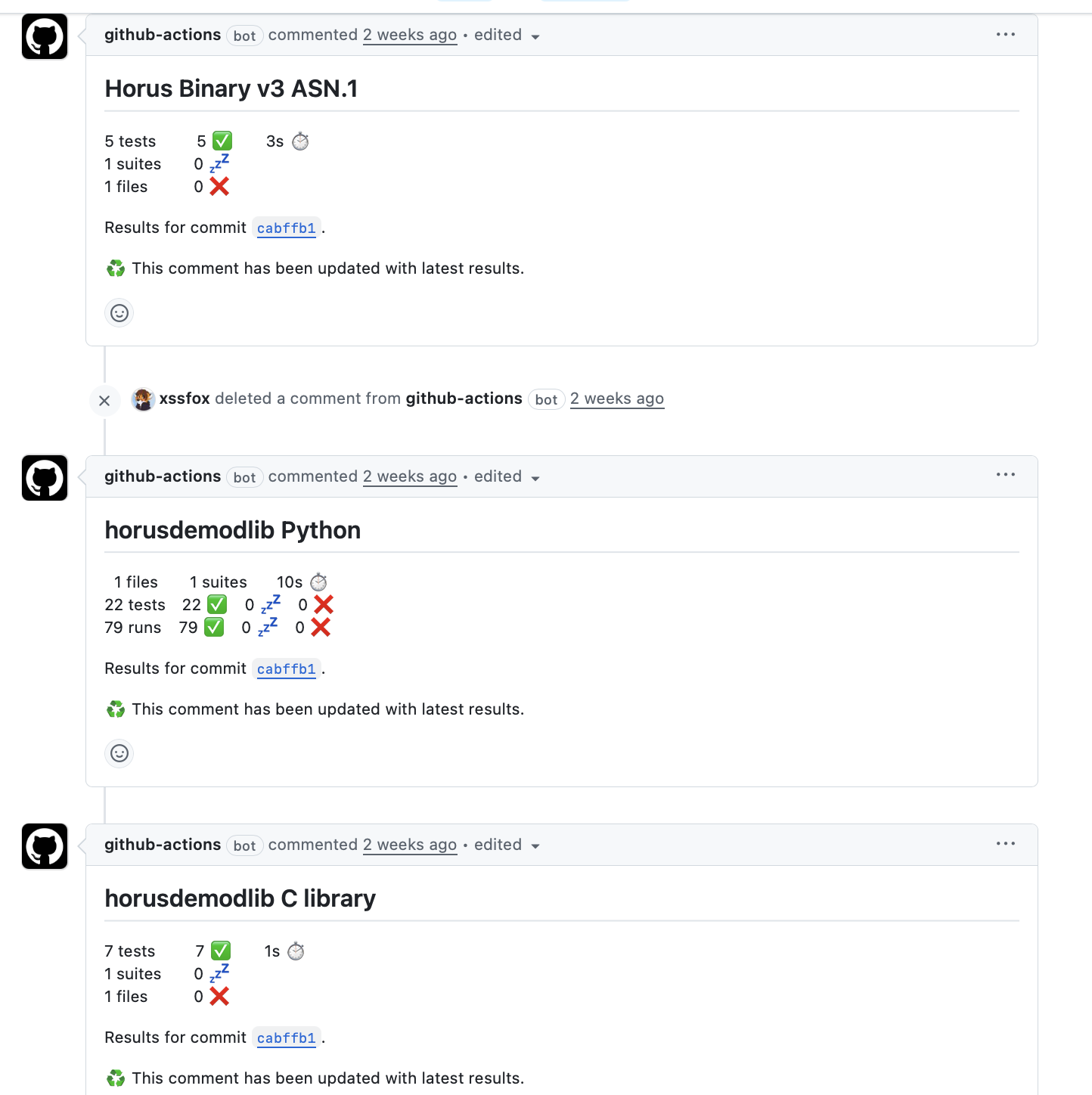

While there were a few manual test scripts, these weren’t run as part of any automated workflow, nor did they use any testing framework. These were updated, added to and enhanced to run using Python’s unittest and report as part of GitHub actions workflows.

While not exhaustive, it gives us a lot more confidence prior to release.

Fin.

And that’s it. horusdemodlib and related apps were released yesterday. There’s been numerous test flights leading up to the release (many thanks to everyone testing, both from the transmitting side, and the receiving side). While there’s likely bugs and quirks, I’m fairly confident that V3 is good move forward for the project.

There’s still some things we want to work towards, such as easier receiving CLI app design, Debian packaging and possibly some micro python payloads. First up however, I’m taking a nap.

Further reading

- Horusdemodlib GitHub Repo

- Horus Binary v3 ASN.1 README

- Horus GUI

- AREG Project Horus

- SondeHub Amateur

-

Informally known as UWUs within the SondeHub team now. ↩︎

-

Currently the apps assume certain configuration files and data files exist, so you are best off following the install instructions here. ↩︎